Big Test: Canon EOS C80 and C400

Posted on Nov 13, 2024 by Pro Moviemaker

Canon mounts cinema camera attack

The first full-frame Cinema EOS cameras with RF lens mounts boast next-generation tech and are competitively priced

When Canon launched the Super 35 EOS C70 hybrid camera three years ago as the new entry-level model into the Cinema EOS range, it was the first movie model to use the RF lens mount as debuted on the EOS R mirrorless line.

Back then, we predicted it could lead to a whole new range of full-frame Canon EOS cinema cameras, as the RF mount allows for faster apertures and better communication from lens to camera, for improved features such as image stabilisation. A short flange distance also means it’s easy to adapt other optics to fit, like the plentiful, popular Canon EF range or even PL glass. The writing was on the wall for EF mount lenses.

It’s taken until now for Canon to officially abandon EF lens development, fit RF mounts to its cinema primes and move all its new cameras to the RF standard – now in everything from its new pro flagship EOS R1 mirrorless sports camera to crop-sensor consumer models.

The only thing missing was its higher-end cinema camera range, which remained the last bastions of EF. The current full-frame C500 Mark II, as well as the Super 35 C300 Mark III and C200, still use that 37-year-old mount.

Frankly, the launch of the new RF-fit EOS C80 and C400 makes those cameras look decidedly old-fashioned in terms of specs. Both the hybrid-style EOS C80 and the more traditional EOS C400 move the goalposts a significant way.

They are both fast and versatile, packed with all of Canon’s know-how gleaned from its full-frame mirrorless and high-end cinema ranges – and they’re competitively priced. At £5339/$5499 body only, the C80 costs close to what the C70 was at launch.

The C400, coming in at £7799/$7999, is about the same as the C300 Mark III and significantly less than the C500 Mark II, which has already been slashed in price down from its original £16,999/$15,999. Canon has obviously smarted at the sales success of Sony’s FX6 and FX9 and aims to blow the competition out of the water with its latest range.

Sensor siblings

The EOS cameras may look quite different to each other, but they do share a brand-new 19.05-megapixel full-frame BSI stacked sensor with triple-base ISO ratings.

Stacked sensor technology, first used by Sony in its A9 mirrorless sports camera, has proven to be a revelation due to its lightning-quick speed. This made viewfinder lag a thing of the past, unlocking superfast frame rates, a reduction in rolling shutter skewing and a huge improvement in AF. This has now made its way to high-end mirrorless cameras from other brands – which includes Canon and Sony’s pricier cine cameras like the Burano.

Now it’s in Canon’s C80 and C400 and it gives them a massive performance boost that you’ll really notice, not just on the spec sheets, but also in use.

For Canon users wanting to upgrade, the choice now is whether to go with the C80 or C400, as they are each aimed at different users.

The C80 is ideal for smaller production companies or for filmmakers wanting to move up from a full-frame mirrorless to a real cinema camera experience, complete with traditional audio controls and in-depth menus, big cine-style batteries and built-in ND filters. It has many of the rear controls like those on the EOS-1D X pro DSLR or EOS R series, complete with a rear joystick, but there’s no viewfinder. It’s also cheaper than the EOS R1 mirrorless and a better model for shooting video.

It’s a great camera for solo shooters and small crews creating cinematic films and documentaries, streaming or even experimenting with Canon’s VR technology. And it records to a pair of SD memory cards – which are plentiful and cheap.

In comparison, the C400 is a bigger and heavier machine. It offers higher frame rates and bit rates for even more quality than the C80, and adds functions that make it not only great for cinematic shooting or ENG, but also virtual production and live broadcast thanks to genlock and the addition of a 12-pin port to power broadcast lenses. This is a camera that really can do it all, with no compromises whatsoever.

Bit-rate bonanza

Where the C80 tops out at 576Mbps when shooting in Cinema Raw Light files, the C400 is capable of up to a 2.1Gbps bit rate thanks to its additional high-quality (HQ) setting that squeezes every bit of data from the sensor. While the C80 maxes out at 30fps when shooting in 6K Raw, the C400 goes up to 60p, for example. In 4K, the C400 reaches 120p – although it uses a Super 35 crop if shooting Raw – while the C80 struggles to go above 60p.

You can shoot 4K/120p on the C80, but only in a more compressed codec. Both come with a massive spreadsheet of codecs and all the available crops, frame rates and bit rates. Add in full-time AF not working in all high frame rates and it gets complicated.

Some of the best results are a compromise using 4K oversampled from the 6K sensor, which opens up more versatile frame rate choices. We quickly found a codec that did work for us, but it’s good to know there is 6K Raw, for example, when ultimate image quality is necessary – or 4K/120p full-frame for super slow-motion on the C400.

In a strategy that started with the C70, Canon has not crippled the spec of the cheaper camera to protect the sales of more expensive, profitable cameras. The C70’s Super 35 Dual Gain Output sensor that would normally handle Raw files has been upgraded to a new stacked sensor on both the C80 and C400, which can now shoot Cinema Raw Light internally.

There are three base ISO settings – 800, 3200 and 12,800 – when shooting Raw or in Log. Shoot in Canon 709, WDR, PQ or HLG and the base settings are 400/1600/6400, while in standard BT.709 they’re 160/640/2500.

Select which of the base settings to use, or choose Auto and let the camera work it out for you. This lets you achieve optimal signal-to-noise performance even in very low light and it works well. Noise is controlled and even when ISO ramps up, but if some noise does creep in it’s easy to sort in post. These are two great cameras for low-light use.

However, shooting in Raw means the files have no noise reduction in camera. This gives highly detailed shots, but you’ll definitely need to apply noise reduction in post. In a compressed codec like XF-AFC or XF-HEVC S, there is NR added in camera, but this can be adjusted to suit individual shoots. You can also alter settings such as saturation to customise your look.

Although the triple-base ISO sensor leads to some impressive results, it doesn’t quite offer the dynamic range of the Dual Gain Output sensor found in the C300 Mark III. This system works at all ISO levels when each pixel is read out with two different gain levels – one high for controlling noise in shadow areas and one low for better saturation and detail in brighter areas. These signals are electronically combined to make a single image. Maybe this will feature in a higher-end C500 in future?

Gamma school

For a great straight-out-of-camera solution, WDR gamma gives a pleasing and natural look with punchy, vibrant colours that stay just on the right side of being too bold. Again, there are plenty of customisation options. The dynamic range is not quite as high as C-Log2 or 3, but it’s a convenient choice that works well with little tweaking.

When it comes to post, we did have some issues with the MXF files from the C400, but not the C80, when used in Final Cut Pro X. We updated the Canon MXF and Raw plug-ins but the Mac Studio M1 computer still wouldn’t read them and the Edit Ready desktop plug-in didn’t work either. Checking online showed other users had the same problem, but identical files from the C80 were fine! Perhaps it’s a glitch in the Apple matrix. DaVinci Resolve worked perfectly on all files, even though it wasn’t version 19.

Image quality is superb right across the range of settings, with all of Canon’s celebrated natural colour. If you want to go for maximum quality then Raw is ideal, but All-Intra in 4:2:2 10-bit 4K using Log gives impressive dynamic range – with great colours that proved easy to tweak in post. Where the C80 only has two flavours of Raw, the C400 has an HQ version and you can tell the difference – but that’s when pixel-peeping.

Even using 4K/60p in 4:2:2 10-bit Long GOP, image quality is fantastic and the files are robust thanks to the large, modern sensor. Rolling shutter is well controlled, but can be seen obviously in fast whip pans. To eliminate it entirely, the only solution is to use a global shutter full-frame camera, which is currently the domain of high-end Red and Sony cameras that cost significantly more.

Cool AF

The C70 was the first Canon Cinema EOS camera to use the EOS iTR AF X Intelligent Tracking and Recognition autofocus system, which employs deep-learning technology for head tracking in conjunction with face detection. But the AF only covers 80% of the screen – this isn’t the version II Dual Pixel AF technology found in the EOS R5, which covered the whole screen.

Now, the C80 and C400 have the latest Dual Pixel CMOS AF II with EOS iTR AF X that covers the whole screen – and it’s very impressive. The touchscreen has a touch-to-focus feature which allows you to do amazing focus pulls with ease, and touch-to-track, which locks onto a subject and follows them around the screen. This is stated to work for humans and animals, but the latter only covers cats and dogs.

The AF system is customisable in terms of speed and response, so you can dial it in to your needs. When light fades, it struggles a bit on low-contrast subjects, but it is still one of the best out there.

Also included in the model is Focus Guide for manual focusing. This gives a clear indication of which way to turn the focus ring, as well as when the subject is sharp. RF lenses have fly-by-wire manual focusing, so they can never feel quite as good as genuine cinema lenses, although the settings can be tweaked in camera to change the direction and speed of focusing. This is thanks to the advanced electronics featured in these newer RF optics.

Many RF lenses have image stabilisation, which is necessary on the C80 and C400 since there is no built-in five-axis image stabilisation on their sensors. Instead, they use Combination IS – both the Optical IS in RF lenses and digital IS in the camera body – giving a slight crop. This works perfectly fine but isn’t as good as on-sensor IBIS systems.

On such compact camera bodies, there just isn’t room to have both a moving IBIS-style sensor as well as built-in ND filters.

Screen test

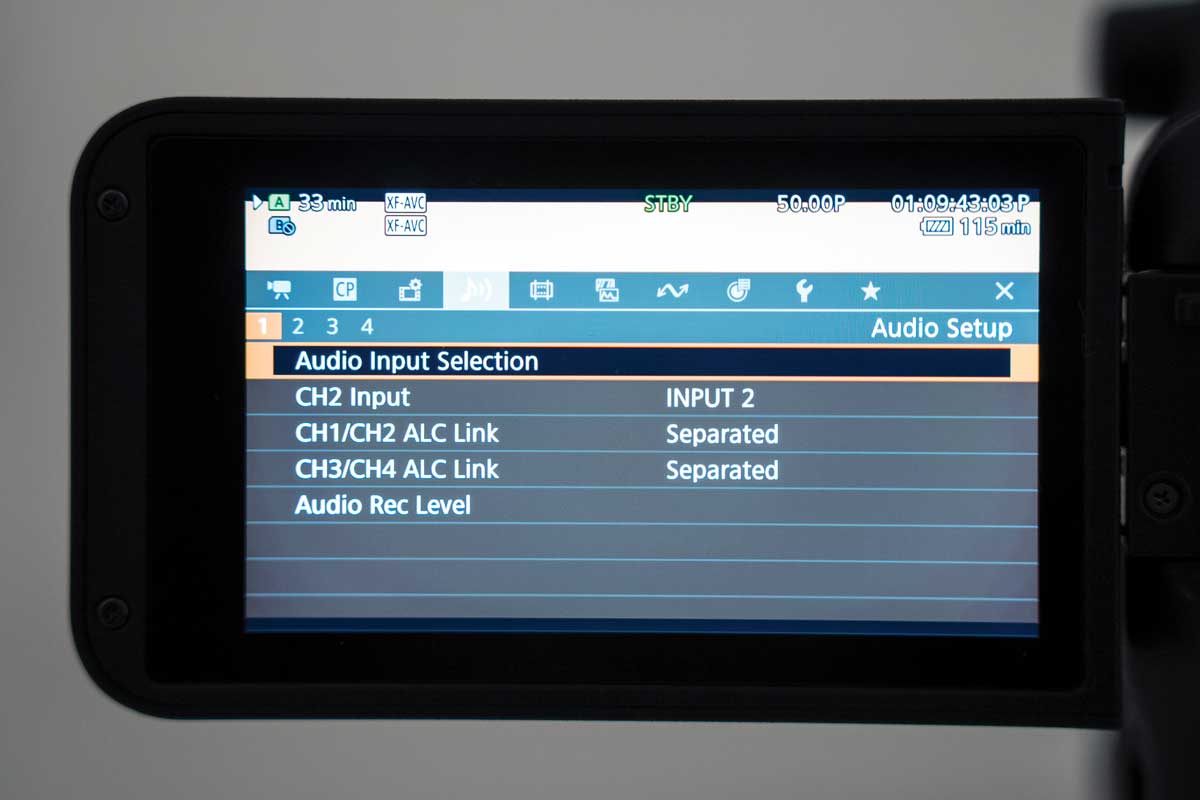

Both cameras have fully articulated screens packed with useful details. There are 13 assignable buttons on the C80 and 18 on the C400, while each model has a multi-functional handgrip and fan ventilation system to prevent overheating. This can be turned off when needed.

The cameras come bundled with a top handle that bolts on securely, as well as XLR shotgun mic holders, but sadly there is no pass-through for the multi-interface shoe or even a second REC start button.

The C80 has a screen that folds out to uncover the audio controls. These are plentiful and command the inputs, which come via mini XLR jacks. The screen is bright, but if you are outside on a sunny day it can be a bit hard to read.

Said screen features waveforms, vectorscope, false colour warnings, adjustable zebras and focus peaking. You can exchange shutter speed for shutter angle and ISO for gain, and there’s also anamorphic de-squeeze support, albeit a limited range.

Canon doesn’t make RF-fit anamorphic lenses and doesn’t allow third-party manufacturers to make full-frame RF lenses, so nothing will fit natively. But the C400 can be fit with a PL mount to accept a whole variety of cinema lenses, including many anamorphics. Just don’t expect a massive range of de-squeeze options when monitoring.

The C400 monitor is a separate screen that connects via a USB-C cable clamped at the camera and monitor end, so it’s easy to take it off and fit to a gimbal handle.

The screen bolts to a new articulating arm that connects to a 15mm rail. This is not a particularly ergonomic or sturdy system, however. It’s like a complicated engineering project to move the screen to where you want it and the USB-C cable easily gets tangled. Rig specialist Vocas has already come to the rescue with a C400 kit that includes a superior system to hold the screen in place.

The C80 now has an SDI output – omitted from the C70 – but this looks like a bit of an afterthought. Both cameras have full-size HDMI and lots of input/output options, with the C400 offering 12G-SDI and all the TV broadcast controls, plus built-in ND filters that go as high as 10x and show little colour shift.

Both cameras can use Canon’s conventional BP-A cinema batteries, but benefit from the newer BP-AN batteries which have more power. On the C400, the front 12-pin port only works with a BP-AN cell.

You can buy batteries with D-Tap outputs to power accessories. The C400 takes aftermarket V-Mount or Gold Mount plates for those large batteries. Use these with BP-A cells to provide hot-swap capabilities for super-long recording sessions, or plug it into the mains with the included AC adapter.

It seems Canon has thought of everything that working filmmakers might possibly need from a single camera and included these features on the C400.

Lens solutions for RF-fit cameras

Although few filmmakers will own a set of cine primes or zooms in the latest RF mount, it opens up a wealth of opportunities for all sorts of lenses. It gives a clear pathway to inspire confidence about future investments in glass. That doesn’t solve the current problem with cameras like the EOS C80 and C400, but there are lots of options.

For users of EF mount lenses, there are lots of adapters on the market that not only fit the optics to the latest cameras but also offer communication with the body and allow users to take advantage of AF, image stabilisation, vignetting and aberration. Basic EF-RF adapters cost around £100/$100, but spend more and you can gain more functionality.

There are locking mounts, speed boosters, tilt-shift converters, adapters with separate control rings to mimic native RF glass and adapters that accept drop-in variable ND filters or polarisers. If you’re a PL user, adapters let you fit the range of lenses going back decades – from the latest Canon, Cooke, Sigma or Zeiss primes to vintage glass.

But if you want to take the plunge into RF lenses, Canon’s own range is the only option for full-frame cameras at the moment. For Super 35 sensors, Sigma and Tamron now have a licence to produce RF fit but these are largely for smaller, consumer-level mirrorless cameras.

One advantage of the large RF mount is that it allows Canon to offer unique lenses that are very fast compared to their rivals. One of these is the Canon 24-105mm f/2.8L IS USM Z (top right) which is the first of a new hybrid line-up of lenses that use powerzoom control as well as offering an expanded focal length range with a constant f/2.8 aperture.

It‘s designed so that event shooters can use a single optic throughout a whole event and add powerzoom control if needed. It’s also a full f-stop faster than the existing RF 24-105mm f/4L lens and offers a wider focal length range than the RF 24-70mm f/2.8 version to provide a fast, multi-purpose optic for filmmaking. We tried it with both the C80 and C400, although we didn’t have access to the powerzoom adapter.

What makes the 24-105mm f/2.8L IS USM Z great for filmmaking are its 5.5 stops of image stabilisation, especially since the C80 and C400 bodies don’t have mechanical IBIS. No other standard zooms offer this and it increases to eight stops with an IBIS-enabled camera body such as Canon’s R5 Mark II mirrorless.

The lens is larger than a 24-105mm f/4 would normally be, but features 23 elements in 18 groups, with four ultra-low dispersion elements and three aspherical ones that reduce chromatic and spherical aberrations. Canon’s Super Spectra, Air Sphere and Fluorine Coatings minimise any flare or ghosting caused by surface reflections on the lens.

This complex design – including Dual Nano USM technology – helps minimise focus breathing and works very well. The lens has two function buttons and an aperture ring and costs £3439/$2999.

There are two adapters that can turn it into a powerzoom lens. The PZ-E2 has a USB-C port and is only compatible with the 24-105mm f/2.8 currently, at £1149/$999. The PZ-E2B also offers a USB-C port, plus a 20-pin connection, for £1529/$1299.

Power comes courtesy of the RF mount or USB-C and there’s a manual-to-servo switch on the side. The powerzoom control allows the lens to go wide or to telephoto with a button press. The new LH-E1 lens holder at £249/$199 also supports the 24-105mm f/2.8 when used in a rig. It’s a totally unique lens, perfect for the new do-it-all Cinema EOS duo.

Canon offers another standard zoom that can take advantage of the large mount: the big, beefy 28-70mm f/2L USM, costing £3299/$2799 and weighing in at 1430g/3.15lb (above left). It’s rather hefty with a 95mm front filter thread and a 104mm/4.09in girth.

Its 19 elements in 13 groups and the nine rounded aperture blades make it optically excellent and its amazingly fast f/2 maximum aperture lets you use it like any prime between 28 and 70mm. It’s certainly lighter and cheaper than hauling that lot around.

Other truly exotic and unique optics utilising the RF mount include the £11,499/$9499 100-300mm f/2.8L IS USM fast zoom and the 85mm f/1.2L USM DS lens with adjustable Defocus Smoothing for portraits. Again it’s not cheap at £3499/$2899, but gives Canon users features they can’t get anywhere else.

The verdict

Canon’s spent so much time creating its high-end mirrorless cameras over recent years that it had started to feel like the Cinema EOS range was getting left behind.

The crop-sensor C200 is legacy technology now and has a lacklustre 8-bit codec when not shooting Raw, the C300 Mark III has a Super 35 sensor and the C500 Mark II is far from the most competitively priced, despite having its price cut – and all still use the older and inferior EF mount.

While the C70 does offer the RF mount, it doesn’t have a full-frame sensor, can’t shoot Raw internally and doesn’t offer the latest AF technology.

When Sony released its low-priced FX6 and FX9, then the Burano, and Red came out with its desirable Komodo 6K and V-Raptor, Canon’s range was left looking a little underwhelming.

The launch of the RF-fit EOS C80 and C400 has definitely changed the game, with their stacked 6K sensors, internal Raw Light recording, high frame rates and suitability for everything from cinema shooting to documentary, virtual reality, streaming, live broadcast – and even virtual production in the case of the C400. And all that for surprisingly affordable prices.

Canon has certainly thrown everything and the kitchen sink at the C400, which has an edge in image quality over the C80 and is more versatile.

The C400 could go down in history as a landmark camera for Canon and the point at which it put itself back at the top of the pile for many users.

The C80 deserves to be a smash hit for run-and-gun documentary, event or wedding shooters since it’s a small yet powerful package that handles brilliantly – as long as you can live without an EVF.

Both cameras boast stunning AF controls, lots of slow-motion options, incredible colour science and the features of a camera designed for people who shoot professionally.

How it rates

Features: 9

Internal Raw, full-frame stacked sensor but no global shutter

Performance: 9

Great image quality and AF, good control of rolling shutter

Handling: 9

Choose your handling style but no EVF

Value for money: 9

They’re do-it-all cameras that can be used for so much

Pro Moviemaker overall rating: 9/10

Stunning start to Canon’s RF mount full-frame cinema range

Pros: All the latest sensor tech, stunning performance

Cons: Limited third-party RF lenses, no global shutter

This review was first published in the November/December 2024 issue of Pro Moviemaker.